Description

History runs in parallel in this work of post-modern fiction, repeating itself in the broken mirror of time.

In one mirror of time, we meet the great young artist and sculptor of the sixteenth century, Michelangelo, whose struggles with his family and Pope Julius II turn his life upside down while creating the monumental statue of David and painting the masterful, immortal frescoes of the Sistine Chapel. In another, we encounter the artist and enforcer of a criminal enterprise in the netherworld of the twenty-first century, also named Michelangelo, the most unlikely of anti-heroes. His fight against a rival criminal enterprise takes center stage in the story, which is told from more than a dozen different points of view.

Michelangelo’s assignment: take down the creator of a dark website called Yellow Brick Road. The creator, known by the code name of IDAHO, is a fathom figure. Nobody is sure if he or she is one or many people, or where the enterprise resides geographically. The stakes are high as Idaho always seems one step ahead of Michelangelo and is able to wreak havoc violently on Michelangelo’s life and family. Who will prevail? And at what cost?

All the while our brave anti-hero, a former middle-school teacher of art and music, is struggling to initiate his young, rebellious sixteen-year-old son Gio into the rites and duties of manhood. Father and son are seemingly always at odds, despite the profound love they share for each other.

We enter the netherworld of the Big Apple at the dawn of the present century when the Internet is just beginning to gain traction; Amazon is only selling books online. And the country is still basking in the glow of innocence and naivete as a new, youngish president has taken office. But in that netherworld, the Dark Web has already emerged in full force with dire consequences. Will justice be served? And if so, by what means?

Excerpt from the opening of the novel

Florence

1488.

Time forks perpetually into countless futures and in one of those futures the die was forever cast: the young boy must leave home and learn a trade. He had turned all of thirteen that year and appeared to show no interest in learning while attending school in Florence. Instead, he had spent his days studying the frescos he had seen in old churches and painting copies of them, and in his spare time trying hard as he could to make friends with other painters. His father, who had once been the podestà or local administrator of Chiusi della Verna and a prominent banker, hated the profession of an artist and often beat the poor boy cruelly. It was a disgrace, to his mind and way of thinking, to have an artist in the house with his four older and younger brothers. He must go. One day the boy’s father decided to send him away for good.

He wrote:

On this day, the first of April, I record that I, Lodovico di Lionardo di Buonarroti, place my son Michelangelo with Domenico and David di Tommaso di Currado for the next three years to come with these covenants and agreements: that the said Michelangelo must remain with the above-mentioned for the stipulated period to learn to paint and to practise this trade, and to do whatever the above-mentioned may order him to do, and, during these three years, the aforesaid Domenico and David must give him twenty-four newly minted florins—six in the first year, eight the second, and ten the third, in all, a total of ninety-six lire.

Michelangelo soon entered the studio of Domenico and David Ghirlandajo, the most famous studio in all of Florence. Domenico was a prolific artist and hard worker with a calm and engaging spirit who inspired the young boy with the moral force of his convictions and his dedication to producing great art. The boy’s struggles with his father receded into the past and his natural talents as an artist began to flourish.

• • •

1502.

One day in mid-February, Michelangelo was standing in the Duomo courtyard gazing upward at the dark clouds in the caliginous sky and the silhouetted block of Carrara marble he had been working on tirelessly for the past five months. Rain was beginning to fall, pinging at various angles the fragmentary outlines of the colossal statue of David he had imagined in his dreams—the noble yet defiant turn of the head, the slender waist, the outsized right hand with swollen veins and fingers, the left arm holding the sling filled with rocks David would hurl at the monster Goliath. Dust was all around him from the chips he had artfully carved away from the block with nothing more than a simple hammer and chisel. His own hands were aching with pain. He wondered how long he could endure without a commission, without the florins he needed to buy food and keep his sinewy body from starving.

Il marmo è sano. The marble is sound, he thought to himself. Small matter if it was now wet with drops of winter rain.

All of a sudden his friend Piero Soderini appeared in the courtyard. Soderini, trained by Lorenzo de’ Medici in the art of politics, had become in time the head of the Florentine Republic as gonfaloniere, or mayor-governor of Florence and the city-state. He had followed the young sculptor’s progress with keen appreciation and had championed his efforts.

For a moment, turning toward Michelangelo, he looked up and saw sunlight breaking auspiciously through the clouds. In his hand was an official document from the Board of Works (Operti). He smiled and read it aloud to the sculptor:

“Members of the Board were pleased. The Honorable Lord Consuls of the Wool Art Guild decided that the Board of Works of the Duomo can give the sculptor Michelangelo Buonarroti four hundred large golden florins in payment of the Giant called David existing in the Opera and that Michelangelo shall complete the work to perfection within two years from today."

“Molto bene! If it’s true, I can now forget about not having enough to eat until I’ve finished. That, my good friend, is truly heaven on earth for an artist.”

• • •

1508.

In early May, he began work on the paintings in the Sistine Chapel, a commission from Pope Julius II that would take him more than four years to complete and cause him much suffering and despair. In a letter to his father, he wrote with fear and trepidation: On the 10th of May, 1508, I Michelangelo, sculptor, began to work on the paintings of the Sistine Chapel.

The labor and demands from the Pope were overwhelming, despite the extraordinary artistic visions that rose from the depths of his being. Sadness and melancholy in his own life found expression, in particular—although he knew nothing of the techniques of fresco—in his painting of the Creation of Man (Creazione di Adamo), based on the Book of Genesis in the Bible.

The painting would become his signature masterpiece, high up in the vaulted ceiling of the chapel: the finger of God, as an old man with a white beard in a swirling brown cloak, reaching out to touch the finger of a naked Adam with a spark that would give life for all eternity to the first man, as told in the Bible. And as scholars would later interpret, God surrounded by the likeness of Eve with as many as eleven other biblical figures depicting the souls of Adam and Eve’s unborn children—figures that scholars would see as embodying the whole of the human race. All of that, yet with two index fingers less than an inch apart crooked between God and Adam, perhaps symbolic of the impossibility of man ever reaching divine perfection, symbolic perhaps also of Michelangelo’s own tenuous and troubled connection to the divine.

The following year, he wrote again to his father sharing his grief: I have gone about all over Italy, leading a miserable life, I have borne every kind of humiliation, suffered every kind of hardship, worn myself to the bone . . . solely to help my family . . .

Chapter 1

I AM CALLED MICHELANGELO

Father, I have sinned.

Under my breath, I mumbled the same words I had spoken more often than I cared to remember in Italian:

Mi perdoni padre, perché ho peccato.

My last confession was a month ago in July, I added in my most humble and contrite voice.

Before speaking, I had made the Sign of the Cross behind the screen, kneeling and feeling ashamed. Father Angelini had read from Scripture, a passage I was not familiar with before we began and I made a mental note to look it up when I got home. And then for the next half hour or so, certainly no longer, I spilled out my guts while Father Angelini listened patiently, his voice sighing and heaving and groaning at times, probably with only passing interest, at the recital of my sins since my last confession. This was the second time in as many months that I needed to confess and make an act of contrition for having offended God and listen to my priest’s words of absolution in hopes of sacramental forgiveness of my church. I was anxious to return home for lunch and see what I could do to salvage the day before it got away from me.

It was early August, hotter than I remembered from previous years, and as I twisted and squirmed in the confession booth, I loosened my necktie slightly and removed my suit jacket and draped it over the arm of my chair. In my left hand I held my beloved Borsalino hat, pure white and soft to the touch, and twirled it around a few times on my index finger. There were still drops of blood curled on my white shirt, stiff and starched like slices of day-old peasant bread, but nothing splattered or blotchy thankfully. The stains would come out later in the wash. They always had before, owing to the good work of my housekeeper María. She knew how to take care of things and I swore to my son that neither of us would be alive today if it were not for her good graces. She was a better Catholic than I could ever be, no matter how many times I sinned and asked for absolution.

My head bowed, my body stooped, I pleaded and begged for mercy and God’s forgiveness, although I had no legitimate right to ask for either. Perhaps I was simply going through the motions as I had before. When you take another man’s life, even if that man is evil to the core and doing the work of the Devil, a man who has committed heinous crimes and has it coming and deserves punishment by the will of God, you still know you’ve done wrong. Trust me, I said all of that in the booth while Father Angelini squirmed in his chair, rocking back and forth, growing more and more impatient, no doubt wondering how long I would rattle on. Soon I drew my breath, hesitated and began choking up and stumbling badly over my own words, my voice starting to crack like the skull bones of the man I’d shot to death, as tears filled my eyes, and I wept. And I mean, seriously wept. A part of me, through the veil of tears, was hoping for some measure of God’s redemption yet knowing full well in my heart of hearts no such thing would ever be possible, at least not now or ever in my lifetime. In our little world of men and monsters, there can be no acts of forgiveness granted by any good Father who preaches the gospel of Jesus to us, his humble followers, every Sunday morning.

Once I said all that I had to say, or for the life of me could bring myself painfully to say, unleashing the fury of my dark deeds, acts committed to support my family and friends, I headed home from church and navigated the rough, traffic-congested roads that led out of the city and into the boroughs where I’ve been living with my young son. At home I said hello to María, my housekeeper who was preparing lunch (pranzo) in the kitchen, then disappeared into my upstairs bedroom, stripped off my now-soiled clothes and jumped quickly into the shower. The icy-cold water rushing down my back felt good and liberating as I scrubbed myself clean with a bar of rose-scented soap and a stiff wire brush that I used forcefully and aggressively on the full length of my thick arms, legs and chest, butt and back. Somehow, after seeing our Father and spilling out my blood and guts to him, I felt as if I could never get myself clean enough to wash away all the guilt and shame coming over me like a swarm of angry hornets whose nest I’d mistakenly rattled. After exactly twenty-two minutes, I turned off the water, shook my head and toweled off my body as best I could. Specks of guilt and shame were still clinging to my pores and would not dry. Thoughts of church, of worship and prayer, began to spill and roll over the cracks and rocky crevices of my naked body. Soon I changed clothes and placed the pistol I’d used into the lower rack of my bedroom safe, locking it away along with a partial clip of bullets, most unused. I was the only one who had the combination and my son knew that and never questioned why (perché). Which was a good thing to my way of thinking.

Being in church that late summer morning, lighting candles, kneeling and praying for forgiveness and seeking the blessing of the Lord and our good Father, had brought back a flood of memories, all of them steeped in grief and loss. Apart from that day, it would happen each time my son and I attended services at Sunday Mass as part of Holy Communion, when bread and wine are consecrated and shared, which we did faithfully, and I found that I could not stop thinking of my lost but not forgotten wife, whose funeral Father Angelini had presided over with compassion and great understanding. Her untimely death and the death of my unborn daughter at the hands of a hit-and-driver some years back still threw me into nothing short of a demonic rage. I wanted to retrieve that pistol from the safe and go on a shooting rampage, foolishly thinking it would bring her back or make any difference in the larger scheme of things. And to think further, the driver had never been found or identified! Despite all my efforts, with and without the help of the police, he or she still roamed the earth free as a cuckoo bird. You had to be half-crazy to do a thing like that driver did. Stone cuckoo! Justice truly had not been served, had it now? But I vowed it would be one day.

Yes, it would, I told myself. Most assuredly, it would. Sooner rather than later.

Friday night I slept badly, tossing and turning restlessly in bed, my dreams twisted and savage when I bothered to recall them.

• • •

And then Vito arrived and interrupted my plans for Saturday, as he sometimes tended to do, without warning by just showing up unexpectedly next morning at the house. Downstairs, standing in the kitchen, rocking on my heels and drinking a glass of water, I was in a foul, bitter mood but still willing to shine it on when I heard him at the front door.

Buongiorno, come sta? he said. Morning, how are you?

Bene, grazie, e Lei? Good and you.

Bene, grazie. He lifted my spirits a bit by his presence and once inside the front door quickly pulled me aside out of earshot from my son and our housekeeper, for a private little talk, a talk about “business.” I didn’t mind. Not really, not at first. Vito is a man about my age, early forties, swarthy in appearance like me with a huge head of flowing dark wavy hair, slicked back with globs of gel, a man with a sharp, angular and handsome jawline, unshaven on purpose, with fiery dark eyes and always wearing the best Italian-made suit you could find in the city, one of those custom designer jobs from Milan, made of finely-woven wool and hand-sewn buttons on his sleeves and with puffed-up shoulders and a white shirt unbuttoned at the neck, showing a few bristly hairs of male power and dominance. Vito, I hate to say or maybe I like to say, always has a certain stink about him. A fresh stink, as a matter of fact. He’s not a fragrant man by any means. Although he is a pizzaiolo, pizza-maker by trade, he looks in fact like the kind of man who probably muscled and punched and whipped six unfortunate people with his bare hands, practically to death, may God have mercy, all before breakfast, and of course without a single pang of conscience for the pain he’d caused while on his last trip to the big city. You get the picture. He and I, by the way, grew up together. You could say we’re almost like blood brothers in that we’ve each had and still have the other’s back no matter what happens in a world filled with crazies, scumbags and low-lifers.

Saturday is typically the day I like to spend with my son and on this Saturday in particular he was up before me, early and eager to get things rolling, because it happened to be his sixteenth birthday. I had dragged myself out of bed lazily and had a stellar colazione (breakfast) waiting for me downstairs, which María had cooked up to perfection: scrambled eggs and prosciutto, lots of Italian peasant bread smeared with blackberry jam, and two cups of strong Arabic qahwa coffee, instead of my usual shots of Italian espresso for me, a steamed-milk latté for my son, who had just finished eating and started packing the camper van outside in the front driveway to the house. It was a month before school was scheduled to start and I had promised my son a week off from work, maybe as long as ten or eleven days, so we could take a trip on the road together, upstate, well into the back country, God’s country, if I’m right, and get a hard taste of being outside for a change in all the glory of nature and do some much-needed father-son bonding. But now Vito happened to show up.

What brings you here? I asked, knowing full well why he had appeared. Perché (because of) business, he said. As usual. It was a kind of dance we played with each other, like boxers bobbing and weaving and feinting before delivering any big blows, like uppercuts to the nose and jaw, knowing each other’s moves before the real fight began. Is your son around? He asked. He’s always around, Vito. He lives here, with me and our housekeeper. Tell him to bug off. We need to talk private, he said. You mean privately, I corrected his English, which at times was faulty, as the man had never finished high school while I had the benefit of at least a few years at the university not far from our old neighborhood in Little Italy on Hester Street where we grew up together, education being a good thing and something I was hoping I could pass on to my son, who’s now turned sixteen and is wondering if he can take on the old man and beat him to death. The kid is surly as hell, loud and aggressive, wild at heart, which is okay to my mind and way of thinking. A good thing. The classic adolescent rebellion in its early stages, fueled by the curse of raging hormones, right? We’ve all gone through it, haven’t we? I mean, the men in our family. Maybe the girls do too. If I’d had a daughter and if my wife had survived that terrible automobile accident years ago which took her life, I’d know, wouldn’t I? But it never happened that way. Some things in life are taken away from you when you least expect and you never get to recover from the loss, do you?

afterword by tom maremaa

Florence rocks! There is no other way I can phrase it, even if it’s a lame play on words. A city built by artists and artisans, it strains the boundaries of one’s known imagination: how could anything quite so magnificent be possible? And how did it come about? Who were the builders and architects over the centuries? The questions linger and haunt you forever. And eventually they find their way into a work of fiction.

As a young man I traveled to Florence and roamed the city for more than a few days, more like a week or ten days, taking it all in—the Duomo, the Campanile, the Ponte Vecchio bridge that spans the Arno river, the Boboli Bardini gardens which invite you lovingly for a casual stroll when you feast your eyes on their beauty, and of course, the view of the sunlit Tuscan hills in the distance. Being there, the streets and buildings looked strangely familiar, as if somehow I’d been there before, probably in another life, I came to realize, as a builder, stone mason, brick-maker, or perhaps even an apprentice sculptor working with Carrara marble from the Fantiscritti quarries, the same marble Michelangelo used to carve David. Matter of fact, when I saw Michelangelo’s David at the Galleria dell´Accademia on Via Ricasoli number 60, I felt as if I’d seen it before while the sculptor was carving the 17-ton, pearly white figure from stone. I was awestruck. And the feeling has stayed with me for almost a lifetime.

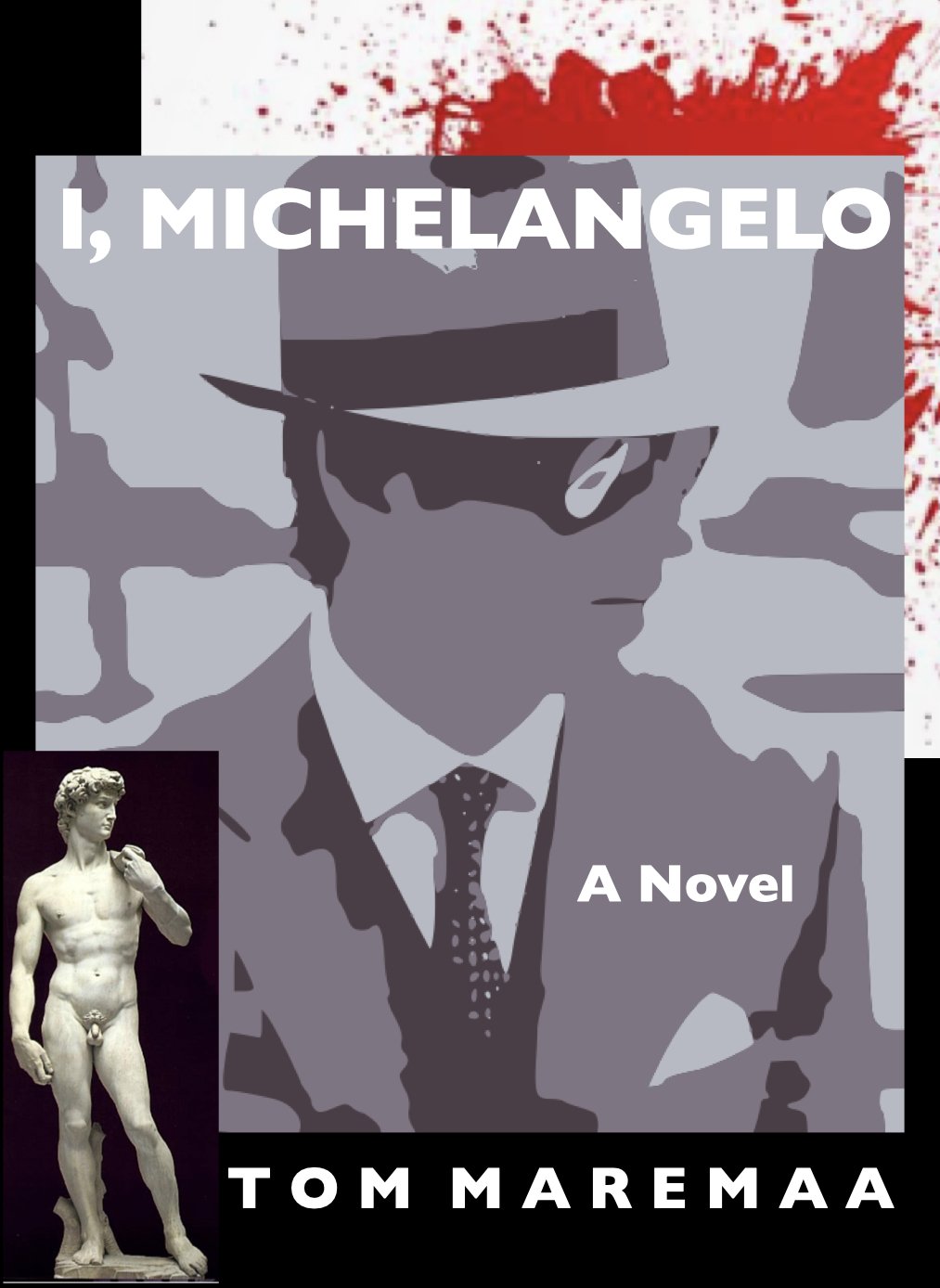

As it happened, I was working on another novel when I, Michelangelo, came on to me unexpectedly with a surge of remembered emotion and passion. I knew then I had to give it voice, listen to the characters and allow the novel to write itself without a huge amount of interference on my part, at least not consciously. Passion always dictates form and in this case the form was not generic fiction but something entirely original in voice and storytelling. The account of a man who teaches middle school, then loses his job and his pregnant wife in a hit-and-run accident, and breaks bad with a criminal enterprise to support his young son and rebuild his life and family was strong enough to have a life of its own. It felt like a story that had to be written, although I never envisioned telling it from so many different points of view. It was a technique I had never employed before in my previous works of fiction, and felt strange at first, yet appropriate to the narrative. These things happen, I realized: you start on one book and another surfaces and makes itself known and demands to be written.

Oddly enough, on walks and while lying in bed at night I kept reciting the lines from Eliot’s Prufrock, which have always haunted my imagination:

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo

Why? And who was this Michelangelo? And then right there, the character of Michelangelo D’Antoni emerged, almost full blown. He began to walk around our house from room to room, smiling and laughing a bit, and even accompanying my wife and I on our walks outside to catch a breath of fresh air. He seemed friendly and engaging, a decent fellow, with a lot on his mind. He also seemed to have a dark side. Once characters step inside your house, they almost become family and you begin to treat them as such. Memory knows and knowing remembers: I had grown up with a lot of Italian kids in my old neighborhood and particularly in school and knew them well, loved playing kids’ games with them, hanging out, talking about girls and sports, and getting a pretty good feel for how they thought and acted and what they seemed to want from life. The mystery to be solved was what they had all become, in time, as they grew older and took on life’s myriad burdens and sorrows. What happens to a man like Michelangelo D’Antoni? He makes certain choices with his life and suddenly finds himself in the thick of a plot to take him out by a force he barely comprehends. All the while he is trying to bond with his young son Gio who has turned sixteen and is feeling his oats, running a bit wild, challenging the father’s dominance and control. As I read the biographies of Michelangelo the painter and sculptor, I noted the same conflicts and struggles with fathers, both his own and the Holy Fathers who sat in their papal thrones in the sixteenth century in Florence and Rome.

And then there was this thing about Florence. I felt compelled to add to the story the events of the young sculptor’s life, particularly the creation of the statue of David and the painting of the Sistine Chapel. I am not sure exactly why, but I’m grateful to the many sources and material I discovered:

Irving Stone’s most excellent novel, The Agony and the Ecstasy.

Michelangelo Buonarroti by Charles Holroyd.

The Lives of Artists by Giorgio Vasari (In translation by Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella).

From Marble To Flesh. The Biography Of Michelangelo’s David by A. Victor Coonin.

Michelangelo by Romain Rolland.

Under the Tuscan Sun by Frances Mayes.

Stones of Florence by Mary McCarthy.

The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje.

I also wish to acknowledge and credit the lyrics from Goodbye Yellow Brick Road by Elton John and Bernie Taupin.

Beyond these credits, I also wish to thank my wife Mimi who was there on every page with her great suggestions, comments and criticisms, as always with any of my works of fiction that I’ve shared with her. In particular, her help on this story immeasurably improved the narrative for a global audience of readers. Enjoy!